To Penguins

/Two days had passed since we sat with thousands of Magellanic Penguins on the Cabo Vírgenes peninsula—an edge-of-the-world expanse that juts out into the Atlantic Ocean. The passing joke that had turned into Portland to Penguins—and as much an end goal as any geographical point—was now behind us. We had seen our penguins. Like, 200,000 of them. We’d learned that if you stick your finger towards a curious chick, it will chomp said finger; and that penguins will basically waddle over your toes, should you stand still long enough near one of their major beach-to-nest commuting paths; and that a penguin pooping sounds a lot like a sharply squeezed mustard bottle. We also learned that a Magellanic Penguin’s regular diet of sardines—combined with many a squeezed mustard bottle—can cover an entire windswept peninsula in stank. Portland to Penguins was done, kind of.

Our trip to the penguin colony came at a price. The wind in Southern Patagonia blows west to east. We had exhausted our favorable wind credit detouring clear across the continent to the Atlantic side. Now, we were headed back, against the wind, toward the remainder of our route south, and our other goal—the end of the world/bottom of South America—but more practically, the airport in Ushuaia.

The road to the Chilean border runs at a diaganol. The wind was howling from the west, simultaneously both slowing us down and pushing us into passing traffic. I kept tabs on the cars who passed too close, imagining fist-shaking confrontations once we caught them in the immigrations line. Upon arrival to the border, I lost my nerve, opting to buzz the open car doors and drivers-turned-parking-lot-pedestrians instead—a passive aggressive move that proved surprisingly satisfying. Besides, our mood had shifted. Concrete symbols of progress are always boosting. I reused one of my favorite trip quotes, yelling to Tara, “Any day we cross a border is a good day!” We were riding high, nothing could stop us.

The rub—crossing into Chile—is that immigrations is especially strict about imported foods. A huge portion of Chile’s economy relies on its agriculture, and apparently bringing an apple over the border is so threatening, border control officials insist on stripping you down to your non-perishables. In a car, this is a minor inconvenience as a restock is a mere 100 miles away in the next town. On a bike—however—with food strategically packed for a multi-day, multi-meal journey, it can be heartbreaking to hand over everything considered “real food.”

So, we smuggled. The height of our road-wearied confidence culminated in a single brazen moment: We lied to Chilean immigrations. It was a glorious deception.

It wasn’t all lies. We started the process with honest intentions. When the immigration officer asked if we were carrying any fruits, vegetables, meats or cheeses, we answered SÍ. Our mistake: declaring the goods did not mean we could keep them. Although Tara assured the agent—sweetly—that the onion and two tomatoes were for dinner, nada mas, he still denied their entry. “But it’s pasta night,” she added nervously. It didn’t matter what night it was or that we were traveling by bicycle, we would have to give up the goods. If we preferred, he added, we could eat them right then and there.

“The onion?” I asked. “Como una manzana?” Like an apple?

“Si quieres.” He said. If you want, otherwise hand it over.

I tried to look past his aviator shades for any recognition of the humor in his suggestion, but Latin America isn’t big on irony and customs officials aren’t big on jokes.

We politely passed on the raw onion.

“And, do you have an apple?” He asked, surely triggered by my mentioning it.

We did. And with the evidence nearly poking out of Tara’s bag, we fessed up and ate both our last Granny Smith and the remaining tomatoes in the same way—like apples—wiping our dripping chins to the amused line of cars awaiting their own inspection.

Stripped of our only produce, we shared a nod that we would not be giving up anything else—border tax paid. I left my far bag closed and thus concealed its contents of our lone package of salami and the remaining quarter of a mushed block of cheese. Contraband, but we would be damned if we were going to keep entertaining the cars with our forced feeding. I did a faux search and pulled out all my best clueless items. Can of tuna, señor? His head shake said that I could keep it and that I was an idiot. Oatmeal? He asked a third time if there was anything else. He patted my pannier.

“Vegetables, carne, salami, cheese?”

Tough to play the translation card while he’s speaking English, but I stuck to my resting confused face, now well-honed.

Anyway, there would be no returning to the truth—it would have been awkward. At previous Chilean borders we had been required to remove all the bags and feed them through a conveyor, but we were betting on that not happening this time. The line of cars was too long and we were too sly. Tara handed over our uneaten onion and we pushed our bikes into Chile, back out into the wind.

We’d only made it fifty feet down the road before our border agent came running after us. He was irritated. Tara and I hadn’t decided on exactly what tact to take upon his arrival. We were hardly making a getaway. My helmet had been blown off my head and was floating in the drainage ditch behind me. Tara frantically dug through bags in search of her missing hat, careful to not lose anything else to a strong gust. All while I struggled to hold up a bike in each hand against the wind—offering suggestions as to where she should look by pointing with my hips. As he approached, we decided to stick with the increasingly convincing act of “hapless and confused.”

It turned out to be nothing. He just needed to confirm our exit stamps. We retrieved our passports and directed him to the proper page. There was actually a part of me that was hoping he would discover the salami—let’s get detained! Who cares?! Make this interesting! He grunted at our stamps and walked back to his post. We’d made it, again.

Seeing no need to flee the scene, we stopped at the border’s half-constructed “cafe” to regroup over a cup of coffee. Cheers to Chile, or something. A short five minutes later our immigration agent entered the cafe, aviators still on. A gust whipped open the door, revealing him standing in the doorway. It felt like an incredibly low stakes horror film. Here we go agaiiiii...it was his lunch break. He ignored us and sat at a nearby table. We made sure to closely monitor our conversation anyway, lest we give ourselves away.

Outside and back on the bikes, we were treated to a southeastern turn in the road. The wind was at our backs. The vast expanse of golden pampa grass now bent in our favor. Ahead, the Straights of Magellan marked a blue strip on the horizon, and beyond that, shimmered Tierra del Fuego—the long-sought promised land now within sight. Riding with a tailwind is almost silent—a feeling of quiet weightlessness like the apex on a playground swing. In the moment, it was lifting. So was the caffeine from the instant coffee we have grown to love. So was the feeling of being so near the official end of our trip. So was the elation of having damned the man. All of it rose in my chest. I let out a yowl that was pulled away by the wind. Tara beamed. What a rush. What rebels. What seasoned biking warriors. Our second to last border crossing of nearly two dozen. The afternoon’s picnic could not possibly have been sweeter, high on 150 grams of pure Argentinian salami.

Of course, no good buzz lasts forever. The road eventually curved back west. The wind came with it, all but stopping our progress. It was a reminder that our trip was not quite over. And that moments of reflective completion bliss will come in waves, not necessarily in one steady crescendo. We called it for the day and spent the night in a bus stop/refugio a few feet from the highway—drifting off to the rattling of passing semis and the absurdly long light of summer days at high latitudes. The next morning we made a go of riding directly into the wind, but only made it halfway through the day before eventually hitching with a farm truck bound for Punta Arenas.

And here we are now, in Punta Arenas, the southernmost city in Chile. We have flights booked for mid-February out of Ushuaia and technically more time left than miles to ride. There is no hurry. All of the Patagonia mega attractions are behind us: Torres, Fitz Roy and the Perito Moreno glacier. We have made it to our own mega attraction—the penguins. All that’s left to do now is enjoy the remaining miles, the desolation of Tierra Del Fuego, a few more penguins, and whatever delicious goods we’ll bravely carry over our last border into Argentina.

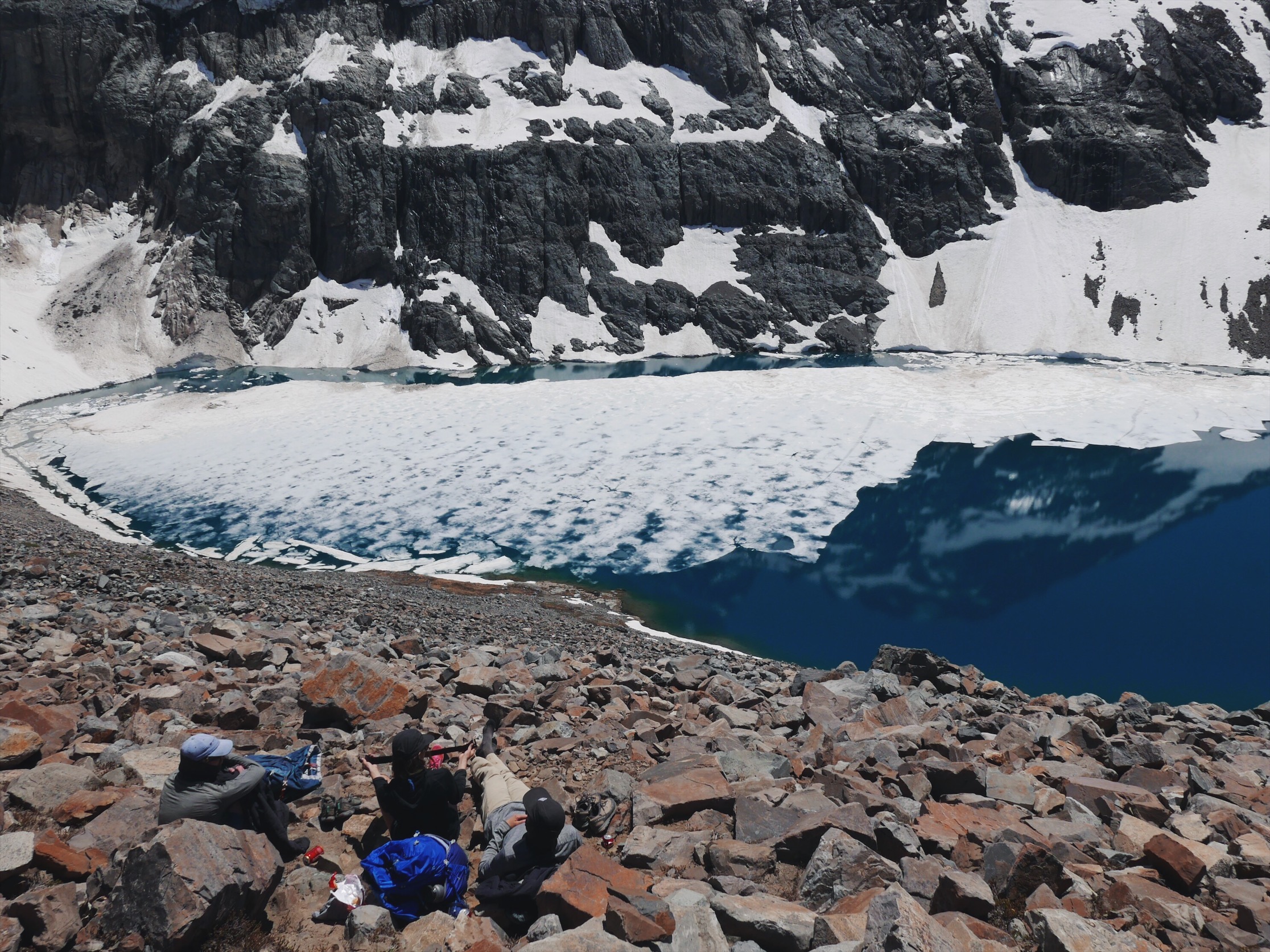

A 3:45AM wake up had us cresting the last ridge just as the very top of Fitz Roy illuminated. The sunrise gradient grew—from the tip down—eventually painting the entire horizon. Much like other hike excursions on this trip, we ended up in the right place, at the right moment, without planning anything beyond T-bone’s early call time.

Laguna de Los Tres, Los Glaciares National Park.

Fitz Roy is a climbing mecca. Many climbers stay for months during Patagonia’s summer season, but spend much of their time in the backpacker haven village of El Chaltén awaiting weather windows. The “real climbers” look especially capable in their ice climbing boots, heavy bags and dangling gear paraphernalia. Here Aidan holds up an extra pair of socks—the only additional gear we brought on our hike.

Neighboring lagunas foreground for the seven peaks comprising the Fitz Roy skyline. Fitz’s 5,000-foot granite fin is an impressive sight to behold. We later watched the film A Line Across the Sky documenting climbers Tommy Caldwell and Alex Honnold’s quest to traverse all seven peaks in a single expedition—a feat that only seems more absurd having sat underneath them.

Look out, people!

The only way to access the Cabo Vírgenes Pinguinera is on a looooong, dirt road in exceptionally bad shape. We’d initially planned to ride the route before learning that “looping” the peninsula was not possible, necessitating a 4 or 5-day out-and-back. There is nothing more than a massive oil refinery and a lot of sheep along the way, so when we learned—additionally—of the lack of potable water available, enthusiasm for riding really waned. All that is to rationalize the car we rented for the day. Although a nerve wracking 7-hour round trip—due to only half understanding the rental agreement and lack of anything we know to be insurance—the 250,000 mating pairs of Magellanic penguins were absolutely worth it.

March of the f*&^ing Penguins!!!!

There are a few sandy superhighways connecting the beach to the penguins’ nests. They wander/waddle these routes in order to feed in the ocean before returning to share their catch with the kiddos. If you’re patient, they’ll happily go about their commute like any other day.

Penguin chicks! A stationary bunch, these chicks spend a lot of time in the sun waiting for the fuzz to turn to fur, and mom and dad to come back with something to eat.

But they don’t discriminate as far testing out potential food sources...

Finger bitten, lesson learned.

A sign warning drivers of the wind. The tree is being violently blown [by the wind.] There are hardly any trees here. Presumably this sign is depicting why, as well.

Overnighting at one of a number of highway puestos—emergency roadside stops—in the Argentinian pampa. As some of the only vertical structures (read: wind blockers) around for miles, cyclists are welcome to camp on their leeward side. Miguelito was perfectly happy to have a few neighbors.

160 miles of the Ruta 40 lies between Puerto Natales, Chile and Rio Gallegos, Argentina. Essentially, the entire west to east span of South America, at this point. Though we had the wind at our backs, a long-abandoned paving project made for slow going. One of only a dozen buildings on the entire route, this puesto was a welcome sight. Luis, the caretaker, lives in a trailer out front with his Shih Tzu “Gordita” (little fatty). He was slightly suspicious of us at first but warmed to Tara’s Spanish (or just Tara) and ended up showing us to our very own trailer/room. He even fired up the water heaters for a round of showers. What a guy!

Presumably, we will not sleep in separate twin beds nearly as often once we’re back in Portland.

Roadside diner.

Laguna Torre, Los Glaciares National Park. Cerro Torre Tower pulled the cloud covers over its head minutes before we arrived. We didn’t mind. The natural beauty of Patagonian mega attractions is often outshined by the world-class people watching.

Torres del Paine National Park. Tara’s alarm sounded at 3:30AM. Thirty minutes later, we left our riverside campsite in the pitch black, navigating the road into the park with headlamps. We could see the Torres towers (back right) glowing against the then clear, dark sky. Savoring the windless moment, the last of the night’s stars seemed to slide behind the towers as our perspective changed at bicycle speed. Well worth the wake up.

Cuernos Del Paine. Cuernos means horns.

Borrowed a lightly-used cow field for the evening. The tent zippers have stopped working almost completely so the extent of our bug protection is a desperate prayer for no bugs. Prayers answered this evening.

Photo Drunk: When it’s all just too much and you can’t stop taking pictures/be bothered with your bicycle.

Patagonian Weather: you like it or not.

Matchy matchy!

Wind protection for one.

The Torres del Paine Park is truly spectacular, although it’s hard to know how to best approach it on a bicycle trip. The crowds are absurd, as are the regulations surrounding the hiking and camping. We opted out of the famous multi-day treks and were very happy to have a few real good (real quiet-ish) moments to ourselves. Here Aidan is literally blown away.

If we come back with Mom and Dad maybe we can stay at a hotel. This hotel.

Fisherman and the Pacific outside Puerto Natales.

Another incredible Patagonian attraction. The Perito Moreno glacier delivers as a spectacle. Warm temps and flowing rivers meant the glacier was especially active. Platforms allow for easy up-close viewing as massive 100-foot tall chunks calve off on cue. Keep an eye out for footage from the 1000+ Gore-Texans pointing their wide angle GoPros at the glacier. Sound on for commentary.

Perito Moreno is the only glacier in Patagonia that’s actively advancing rather than disappearing. While, the exact reason for this is a matter of debate, it’s still nice to see a bright white glacier rather than the hundreds of muddy, melting piles we’ve seen elsewhere.

Going full tourist. Tough to poke fun at the busloads of noobs when we’re the ones who forgot to bring sunscreen to the world’s largest tanning bed, but we managed.

![A sign warning drivers of the wind. The tree is being violently blown [by the wind.] There are hardly any trees here. Presumably this sign is depicting why, as well. ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56ec63414d088eba2c0987ba/1517502529238-GWW794FFWJT48E7OBUJZ/IMG_2217.JPG)

![Translation: Don't hate me just try to forget me. [Rambo break] I am guilty of your tears.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56ec63414d088eba2c0987ba/1496777753337-1HDILL7BZYXT8MXRU9GW/IMG_1274.JPG)

![Simon of Taxi Tandem Tour is riding [a tandem] with an empty seat, picking up passengers as he makes his way south to Argentina. ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56ec63414d088eba2c0987ba/1490992111017-M03WMJ2HXRIHWCRTJ97S/IMG_0863.JPG)